I’m not talking about dance lessons. I’m talking about putting a brick through the other guy’s windshield. I’m talking about taking it out and chopping it up.

-- Royal Tenenbaum

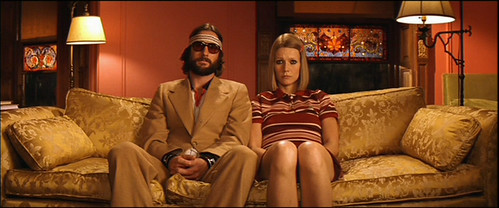

Christian Lander has ranked Wes Anderson among the top things that white people like.[1] Fortunately Anderson’s films are not restricted to a particular ethnic audience, but they are ironic and a breath of fresh air away from typical Hollywood releases. Through humor, tragedy, irony, and excessive attention to details, Anderson tells the story of a New York family recovering in the wake of failure. The characters’ experiences and encounters provide mediations of philosophical themes in the film: The Royal Tenenbaum. In typical Anderson style, this paper will begin with backstory and introductions before sequentially exploring the narrative.

Opening Credits

A philosophy graduate from the University of Texas, Wes Anderson has imaginatively and uniquely created a library of films in which many of his colleagues acknowledge him as a young filmmaker with the tools of continuing his success filled career. In an article for Esquire, Martin Scorsese classifies Anderson as a filmmaker who is capable of garnering legendary respect amongst filmmakers. Scorsese commits, “Wes Anderson, at age thirty, has a very special kind of talent: He knows how to convey the simple joys and interactions between people so well and with such richness. This kind of sensibility is rare in movies.”[2] Scorsese and other material filmmakers began their careers in the movement titled New Hollywood - a rare bunch of filmmakers who emerged in the 1970’s. These auteurs were given the artistic freedom and were not bound by constraints such as genre.[3] Scorsese and many of his generation uniquely developed a timeless library of films. A club, many predict, including Scorsese, that Anderson will soon join.[4]

The Royal Tenenbaums was birthed out of Anderson’s desire to film in New York; a city to which he had recently moved before the shooting of the film. The film portrays a stylized and almost mystical New York City. Anderson’s New York feature streets that do not exist and purposefully removes all of the buildings and monuments representative of the city. Ironic and fantastical detail provide an environment where the characters interact. These independent, interpersonal interactions become the focus of film.

The Royal Tenenbaums features many characters. All with their individual issues and problems. Royal Tenenbaum is the patriarch; He left the family, but decided to return out of desperation. He had no other place to go. A death threat caused him to secure a space in Richie’s room, but once the truth of his health situation surfaced, Royal was removed from the house, along with his partner in crime: Pagota. After Royal’s initial departure from the family, Etheline, his ex-wife is left with the priority of raising the three kids.

The three Tenenbaum children share famed childhoods. Richie is an all-star tennis player, Chas deals in international finance, and Margot is playwright. All are child geniuses, but their success falls to failure. Thus, their identity is in flux by adulthood. The once teenage prodigies have awoken in their thirties to find themselves desiring adolescence again. All three kids, after experiencing a type of failure, return home, where the authenticity of their individuality is actualized. In fact, it is not only the Tenenbaum children who experience this transformation, but nearly all of the characters share in this self actualization, starting with Royal.

Interpreting Film in Wake of Philosophical and Cultural Thought

Films are vehicles for differing analyses. Some may illustrate philosophical concepts; others might mediate philosophical themes. Contrary to many or most films developed and released by major hollywood studios, Wes Anderson thoughtfully directs The Royal Tenenbaums. His auteur attention to detail allows the audience to interpret the film through multiple lenses. This paper seeks to unite possible philosophical readings of the film, yielding a understanding of both the film’s scenes and the writings referenced. In essence, the film helps in calibrating the horizon of thought separating philosophers.

One of Hans-Georg Gadamer’s most influential contributions to the history of philosophy was his analysis of horizons. A horizon is the situation, or position, from which everything can be seen.[5] Due to diverse presuppositions and experiences, viewers of The Royal Tenenbaums will read the film differently. Although one’s reading might be different from another’s, it is important for them to explore each other’s horizons. On the path towards understanding, we do not presuppose agreement when stepping into another’s horizons, but find it a necessary part of the journey.[6] By placing ourselves within another’s horizon we can start to understand the particular situations and instances of understanding.[7] It is by viewing The Royal Tenenbaums from multiple horizons that an audience can reach an understanding of the philosophical themes mediated.

There are several readings or philosophical mediations available to the audience in its analysis of the film. The following readings complement the viewing of The Royal Tenenbaums. They include, but are not limited to, the writings of Pierre Bourdieu, Anthony Giddens, Berys Gaut, Richard Kearney, and Søren Kierkegaard.

Anthony Giddens was born in 1938 in London. Some classify Giddens as Britain's most well known social scientist since John Maynard Keynes. He was professor of sociology at the University of Cambridge before accepting the position as Director of the London School of Economics in 1997.[8] Berys Gaut, also from the UK, is reader in philosophy at the University of St. Andrews. His research interests include the philosophy of film and film theory and aesthetics.[9] Finally, Pierre Bourdieu is internationally renowned for his work at bringing the academic disciplines to solve basic daily problems. He sees the rise in journalism and entertainment as a movement away from necessary intellectual progression. Educated as a philosopher, Bourdieu is a self-taught anthropologist and sociologist.[10] The writings of these prolific thinkers, along with others, serve as an insight in to reading Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums.

An Individuals History

One’s life story is a random mixture of a uniform series of events. In fact it is the randomness that makes one’s individual story memorable. An autobiography, according to Richard Kearney, is achieved by shedding light on both past events and future objectives. An individual’s identity is inherently narrative, and takes into account their past and projected future. In a way, story humanizes time by organizing or unifying what seems to be divergent moments into a cohesive account. The excessive details included in The Royal Tenenbaums reveals aspects of each character. [11] In introductory sequences, Chas is shown playing drums. The act of playing drums seems unnecessary in the development of his character, but the included detail illustrates the reality of the relatively unorganized nature of human narrative. The narrative of an individual’s life should be complex; complexity within narrative is closest to reality. As illustrated, Chas is not only successful in business, but he pursues other interests as well. Richie is similar. Painting was a talent Richie enjoyed from a young age, but never developed, like he did tennis. The younger son kept a small studio in his bedroom where he would paint pictures composed of family members and events. Although painting is not a successful interest for him, like tennis, this activity illustrates the complexity of the human experience. Peripheral interests are not pointless, rather they are important details in an individual’s story.

In “The Biographical Illusion,” Bourdieu describes a person’s life history as a series of events that correlate from one action to the next, but a mere record of these events alone fail to comprise an individual’s identity. A biographical look at a person’s life is not limited to only their major experiences but their distinctive activities - the tucked away events no one knows about. The peripheral or unnoticed aspects of one’s existence must be remembered for understanding their life in its entire complexity.[12] Since adolescence, Margot has hidden her habit of smoking from family and friends. Once the habit was admitted, a hidden aspect of her self was revealed. Margot’s smoking habit reflects aspects of her authentic self both hidden from herself and those closest to her.

Bourdieu also writes that an individual’s external environments or social mechanisms permit certain individual experiences from occurring. The primary or universal institution, common for all, is the proper name. The proper name is the history or structure that an individual is born into. It acts as the support or substance in one’s social identity. “The proper name is the visible affirmation of the identity of its bearer across time and social space.”[13]

A guideline birthed as a result of family lineage, this proper name is one reason failure haunts the Tenenbaums. The three kids have been born into an environment filled with outside pressures due to the institution of family. Both parents, Royal and Etheline, have succeeded in their individual careers. For years, Royal was a prominent litigator until he was disbarred and briefly imprisoned. The proper name provided a detrimental environment within the family, leading all to fail under the pressure.

The proper name is the most evident institutional guideline by which each individual is confined. For the three Tenenbaum kids, their family lineage is passed down from their mother and father. At a young age, the proper name placed constraints rather than freedoms on the three kids. All three failed at continuing their successful and popular childhood identity in adulthood as the name brought along pressure and unattainable expectations. The proper name assures a certain lineage through time. For Chas, his failure is realized shortly after his wife’s death. As a result of the incident, he became overly concerned with the safety of his two sons: Ari and Ozi. His obsessive twitch has led him away from reality. However, self-realization of his problem occurs in the closing scenes of the film, when he acknowledges a problem and admits his need for help.

The pressures as a result of the proper name also effect friends close to the family. From a young age, Eli Cash desired to be the fourth Tenenbaum child. In his attempt to be a childhood genius like his friends, he lives an inauthentic and unrewarding life. At the time the Tenenbaum children experience a lull, Eli succeeds as a successful novelist. It is through personal failure that Eli eventually realizes his unproductive ambitions and in effect joins the Tenenbaum’s in failure. Even in interviews regarding his book, Eli expresses these desires: “Let me ask you something. Why would a review make the point of saying someone’s not a genius? I mean, do you think I’m especially not a genius? Isn’t that-”[14]

Bourdieu paints a second picture describing story. Typical historical thought cannot be applied to an anti-history. Anti-history exists cross-court from normal linear thinking. It is inherently dysfunctional. There is no directed sequence of events that appears to be leading to a goal-a step away from the constraints of viewing life as linear history.[15] The proper name does not exist and neither does other such institutional constraints within anti-history, illuminating the significance of anti-history.

People will naturally begin to view their life as a superhero without considering societal structures that have directly contributed to their current state.[16] Societal norms, structures, and institutions are necessary points of reference when reflecting on and evaluating our own lives. Put simply, we are different because of our society. It is Margot’s habits that differentiates her from her family, but even her habits will not prevent societal structures such as the proper name to restrain her personality. Instead, the institution will always be of constraint to her and her family.

The Individual Relating to Others

In the search for oneself, Anthony Giddens suggests that pure relationships become of fundamental importance in defining relationships. A pure relationship illustrates much of the features present in intimate and emotionally demanding relationships. This title includes marriage as well as select friendships. Pure relationships generally exist within a family structure, in fact they are at times birthed from ones proper name. In “The Trajectory of the Self,” Anthony Giddens has outlined core elements of a pure relationship. Long-term stability breeds intimacy within the pure relationship. Intimacy is the goal of many modern forms of relationships. Intimacy supposes that the two people share both a commitment and a meaningful lifestyle. Royal and Etheline both were perceived as leading interesting and unique lifestyles. Different lifestyles and a lack of time spent with each other yield a lack of intimacy between the couple. These trends open the door for Royal’s departure. Pure relationships imply a commitment to quality. Each individual party must constantly be working towards establishing a culture of intimacy with one another. “Intimacy is usually obtained only through psychological ‘work’, and that it is only possible between individuals who are secure in their own self-identities.”[17] Pure relationships are not rooted in social or economic life but rather are exempt from those restrictions. In contrast to corporate identity or the eastern idea of saving face, pure relationships occur when the two members are encouraged in their self-identity. For example, the birth of a couple’s first child does not anchor the relationship, but rather the birth provides a source of internal drag. Many marriages instead seem to carry on due to the emotional satisfaction a child brings rather than from the two individuals involved. Pure relationships are not tied down. Rather, most relationships fail because the individuals involved no longer promote development of their partner’s identity. In other words, encouragement in one another’s unique self-identity will be cultivated.

Reconsider, instead of unity within the marriage with the addition of three kids, like many couples expect, the result for Royal and Etheline was separation. In the final meeting between the three kids and their father, Royal subtly admits the reason for leaving is in part because of the three kids. An unintentional weight was then placed on the children that continued to haunt the kids into adulthood. This shift in his relation towards the kids later allowed his previous status as father to shift closer to that of a step-parent.

It is nearly impossible for pure relationships to form between parents and their children primarily due to the parent’s position of authority. Step-parents are the exception, pure relationships are able to form between a step-parent and a child. Twenty-years apart from the family left Royal’s relationships with his three kids to model the relationship of a step-father rather than the true father. This contrast is seen in his relationship with Richie. Royal has always favored Richie, yielding a bond similar to that of friends. Time away has allowed a type of friendship to occur between the two characters that might have not originated had a step-parent relationship occurred. The trust and patience given between two friends becomes evident in their relationship in the closing scenes. Richie asks his fathers advice at the hotel, and Royal speaks to him as a friend.

Acting out of Despair: “Not to will to be oneself.”[18]

Richie decides to kill himself immediately after learning of the true history of his sister Margot. Margot has been the receiver of Richie’s affection since they were both young. He has been secretively in love with her but has never admitted his crush. The classification of step-sister made the idea of Richie’s crush an acceptable reality.

The realization that his sister had been hiding much of her history, her true identity, came as quite a surprise to Richie. She is a chain smoker and had many lovers including his best friend Eli. For Richie, the realization that his sister was different than he perceived, brought a moment of panic. Panic leads him to seek escape from his existence by attempting suicide.

Richie’s suicide attempt is best analyzed in light of Søren Kierkegaards: The Sickness Unto Death. Despair is an act of retreat from oneself. The individual in despair is disappointed with their current state, they instead desire to be an ideal they have dreamed up.[19] If bodily sickness leads to death, the sickness of despair is a yearning for death to come. It becomes a way of escaping present reality. To illustrate this sickness, Kierkegaard gives the example of a man who desires to be Caesar but fails. In the wake of failure, the future Caesar becomes disappointed with himself and is led to a state of despair because he is not the person he had dreamed of becoming. Similar despair occurs when an individual becomes disappointed by her lover. But in reality, she is not in despair over her lover, but instead over herself because she is not in the romanticized position she hoped.

Richie discovered that his first and only love was someone different from who he originally perceived her to be. Margot has many secrets. Even in being aware of her secrets, Richie is not despairing over Margot, but himself. In fact, Richie has been in despair for sometime. The realization of Margot’s true identity propelled Richie into a saturated or intensified moment of despair. Richie wants to be Caesar, but he is not. The wish to do away with oneself led Richie to suicide. He is reserving his true feelings and thoughts from everyone. Even as an outstanding member of the community, the familiar mediator between family members, Richie has withheld his despair from everyone. No one knows of his sickness, because he is internally guarding it. The greatest possibility of attempting suicide, comes from men like Richie.[20] Uniquely it was Dudley, a character exempt from emotion, who discovered Richie in the bathroom covered in blood with just enough time to race him to the hospital so his life could be saved. The following scenes involve Richie coming to discern his true identity by communicating his feelings. He no longer is one who withholds his fealings, but is recovering from despair with others. This process involved a healing dialogue with both Margot and Royal. At the end of the film, Richie’s personhood is authenticated resulting in a healing of his sickness.

A Path of Authenticity

“Dread is the psychic state of intense anxiety and concern for one’s ultimate authenticity in the face of unrelenting realities such as suffering, evil and death.”[21] The struggle to live authentic lives is prevalent in all aspects of society. Much of the Tenenbaum’s struggle for authenticity was the result of pressure originating from family history. But it was only through a type of perdition spawned from failure, that the path of authenticity was revealed.

For those living in times of late modernity, questions such as: What to do? Who to be? How to act? are necessary to ask oneself. Anthony Giddens explores these issues in depth. He uses a variety of sources including Janette Rainwater’s work titled “Self-therapy,” that provide insights into these questions. Rainwater’s work in self-therapy is an active self-reflective process where the individual makes choices with the hope of achieving a renewed self-realization. The process of self-change must be realized by the individual. Change cannot occur until he observes a need for self change. Submitting to a process of self-therapy implies a desire to live each moment to its fullest.

“The ‘art of being in the now’ generates the self-understanding necessary to plan ahead and to construct a life trajectory which accords with the individual’s inner wishes.”[22] Everyone has a past, a life history which has contributed to their personhood.[23] In response, self-therapy encourages a dialogue with time - to learn from the past as well as be willing to break from it. In order to improve or grow one must be prepared to break from material items or personal fears that provide the perception of safety.[24] In the closing sequences of the film, Chas throws Eli over the backyard fence after chasing him around the house. Chas then jumps over the wall to join Eli on the other side. As he lays next to Eli on the ground, Chas admits his need for help. Chas’ admonition to Eli reflected his desire for an authentic existence in light of his proper name, past, and future. It was a statement birthed from his desire to change. In segments during the final scenes, each major character reaches at least a stage of resolve allowing an authentic existence to bleed through to their failed state.

Several approaches to self-therapy can assist someone in answering a few questions:

“Where do you want to live?

With whom do you want to live?

Do you want to work?

To study?

Are there any ingredients from your fantasy life that you would like to incorporate into your current life?”[25]

These points of resolve act as presuppositions or starting points in an individual’s search for an authentic existence. With the help of the writings of other philosophers, two main points in the area of self-therapy, introduced by Anthony Giddens, aid in understanding the Tenenbaums’ movement towards a more authentic existence.

It is important for everyone to reflect and evaluate themselves. Self-therapy acts as a reflective project, it is not necessarily who we are today, but who we will choose to make of ourselves. From “Existentialism and Humanism” Jean-Paul Sartre discusses mans resolve in light of their current conditions. With the presupposition that man is without a creator, Sartre compares the human nature to an artist who creates work not out of a formula or a priori, but instead out of their individual choices. He represents the assumption of man as an atheist existentialist.

One man’s existence and subsequent essence is determined by their purpose. Once he acknowledges his own existence, man wills himself and his future. Sartre says, “he (man) is what he purposes to be.”[26] But man is not only responsible for what he is, but his decisions influence all of humanity. Since his choice is good for himself, it is assumed that choice is best for all men. “I am creating a certain image of man as I would have him to be. In fashioning myself I fashion man.”[27] It is in these words that Sartre, presupposes not only man’s free will. But also denies the existence of truth. The lineage of morality is not rooted in a person (e.g. Jesus). But like an artist preparing to create, so man will prepare his life.[28] Sartre also leaves out the social structures such as one’s proper name - the institutions that withhold man from acting in pure freedom.

In his second point, Giddens identifies that an individual forms a trajectory from their past to their anticipated future. This trajectory is organized by the individual working through his past experiences in light of his anticipated future. A direct illustration of Giddens point is found within the work of Charles Taylor. The Canadian philosopher’s work is an “essay in retrieval.”[29] There are certain questions which help make life worth living and confer meaning to individual lives. But in order to understand one’s present situation, one must move forward and back. One must project a future story.[30] Self-therapy, as Giddens describes, allows an individual to work toward gaining understanding of their authentic self. The characters in The Royal Tenenbaums indirectly make a movement towards these identified themes.

Ending Credits

Sympathy v. Empathy, An Audience Response

After watching a film, most audiences end by turning to their friend and saying: "I could really identify with that character." Berys Gaut discusses similar film responses in his article titled: "Identification and Emotion in Narrative Film." The level of emotional response to a film primarily depends on the depth of identification the audience makes with a character or characters. Cinema uniquely gives the impression of reality through the re-enacting of human personalities and experiences.[31] As a result, it appears audiences may both sympathize and empathize with the characters. The fundamental difference in identification is an important discussion when viewing The Royal Tenenbaums, a film composed of identifiable characters.

In identification, the viewer imagines himself as the character on the screen. He comes to care for the character because he sees them as a reflection of himself.[32] Basic logic dictates, however, that two people cannot fundamentally be the same without ceasing to exist.[33] Although a relation occurs, the individual is desiring to see a version of himself in the character. This imaginative identification causes the viewer to care for the character. Sympathetic or empathetic feelings towards the characters are the result. The following discussion will highlight differences between the two distinctive expressions.

The act of empathy requires the individual to actually feel what the the character feels. Gaut believes it is nearly impossible for the viewer, to feel empathy towards an a character.[34] The space created by the medium prevents the viewer to feel sorrowful, angry, or be afraid with the character. Thus true identification requires one to feel and experience the situation with another. Empathizing involves the act of placing oneself into another’s position. On the screen, empathy occurs between Chas and Henry Sherman. Chas empathizes with Henry Sherman when he learns Sherman is a widower like himself. It is easier for the audience to witness empathizing on-screen, than to empathize with the character.

Empathizing assumes feelings of sympathy. Generally, sympathetic feelings occur when the viewer cares or is concerned with the character. Only by identifying can an audience show signs of sympathy towards the characters. One can identify with a character by imagining his sorrow, anger, or fear without empathizing.[35] When viewing The Royal Tenenbaums, it is nearly impossible, in some small way, to not sympathize with a character. Through a form of sympathizing, the viewer is able to enter into a place of experiencing a type of rebirth, like the Tenenbaums. “The character does not grow emotionally, but the audience does because of the way it has discovered that its values are flawed.”[36] As the audience exits the theater, they are urged to evaluate their own present condition as a response to feelings of sympathy towards the film’s characters. Cinema inherently encourages a type of identification to occur. In so doing, the audience is able to relate to the characters and their experiences.

Wes Anderson is a unique filmmaker, a true auteur In all of his films, a conscious appreciation for not only cinema, but also literature, music and art prevail. This interdisciplinary work give force to his films and allow them to work as mediator of philosophical concepts. The Royal Tenenbaums is a film of inherent philosophical depth, it especially raises questions of identity and authenticity. As auteur, Anderson uses the tools of filmmaking to marry filmic form with diverse philosophical content.

Bibliography

Anderson, Wes, and Owen Wilson. The Royal Tenenbaums. London: Faber & Faber, 2002.

Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Biographical Illusion.” Identity: a Reader. Edited by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman. London: SAGE Publications, 2000.

Chin, Daryl, and Larry Qualls. "Ain't Nothin like the Real Thing: Hollywood Comes to New York." PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 25, no. 1 (January 2003). http:// www.jstor.org/stabe/3246523 (accessed April 16, 2009).

Film Monthly. The Royal Tenenbaums Press Conference with Wes Anderson. March 9, 2002. http://www.filmmonthly.com/Profiles/Articles/WAnderson/WAnderson.html (accessed May 11, 2009).

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Relevance of The Beautiful: And Other Essays. Edited by Bernasconi, Robert. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Gaut, Berys. “Identification and Emotion in Narrative Film.” Philosophy of film and motion pictures: an anthology. Edited by Noël Carroll and Jinhee Choi. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

Gaut, Berys Nigel, and Dominic Lopes, eds. The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Giddens, Anthony. “The Trajectory of the Self.” Identity: a Reader. Edited by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman. London: SAGE Publications, 2000.

Hill, Derek. Charlie Kaufman and Hollywood's Merry Band of Pranksters, Fabulists and Dreamers: An Excursion Into the American New Wave. Harpenden: Kamera Books, 2008.

Honderich, Ted, ed. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Johnson, Patricia Altenbernd. On Gadamer. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2000.

Kearney, Richard. One Stories. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Kierkegaard, Søren. The Sickness Unto Death. Edited by Hong, Howard V. Translated by Hong, Edna H.. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Lander, Christian. Stuff White People Like: A Definitive Guide to the Unique Taste of Millions. New York: Random House, Inc, 2008.

McLemee, Scott. "Locating Bourdieu." Inside Higher Ed, June 23, 2005. http:// www.insidehighered.com/views/mclemee/mclemee38 (accessed May 16, 2009).

Mudimbe, V.Y. "Reading and Teaching Pierre Bourdieu." Transition no. 61 (1993). http:// www.jstor.org/stabe/2935228 (accessed May 2, 2009).

Piechota, Carole Lyn. "Give Me a Second Grace: Music as Absolution in The Royal Tenenbaums." Senses of Cinema no. 38 (January 2006). http:// archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/06/38/music_tenenbaums.html (accessed April 20, 2009).

Pollitt, Katha. "Pierre Bourdieu, 1930-2002." The Nation, February 18, 2002. http:// www.thenation.com/doc/20020218/pollitt (accessed May 1, 2009).

"Professor Anthony Giddens." news.bbc.co.uk. http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/ events/ reith_99/giddens.htm (accessed May 15, 2009).

Reavley, Gordon. "Film Review, The Royal Tenenbaums." Scope (February 2003). http:// www.scope.nottingham.ac.uk/filmreview.php? issue=feb2003&id=689§ion=film_rev&q=Tenenbaum (accessed April 27, 2009).

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “Existentialism and Humanism.” Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

Scorsese, Martin. "Wes Anderson." Esquire, March 1, 2000. http://www.esquire.com/ features/wes-anderson-0300 (accessed March 18, 2009).

Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Weiner, Jonah. "Unbearable Whitness: That queasy feeling you get when watching a Wes Anderson movie." Slate, September 27, 2007. http://www.slate.com/toolbar.aspx? action=print&id=2174828 (accessed May 1, 2009).

[1] Christian Lander, Stuff White People Like: A Definitive Guide to the Unique Taste of Millions, (New York: Random House, 2008), 11.

[2] Martin Scorsese, "Wes Anderson," Esquire, March 1, 2000, 1. http://www.esquire.com/features/wes-anderson-0300 (accessed March 18, 2009), 1.

[3] Derek Hill, Charlie Kaufman and Hollywood's Merry Band of Pranksters, Fabulists and Dreamers: An Excursion Into the American New Wave, (Harpenden: Kamera Books, 2008), 24.

[4] Martin Scorsese, "Wes Anderson," Esquire, March 1, 2000, 1. http://www.esquire.com/features/wes-anderson-0300 (accessed March 18, 2009), 1.

[8] "Professor Anthony Giddens," news.bbc.co.uk, http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/events/reith_99/giddens.htm (accessed May 15, 2009).

[9] Berys Nigel Gaut and Dominic Lopes, eds., The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, (New York: Routledge, 2001).

[10] Katha Pollitt, "Pierre Bourdieu, 1930-2002," The Nation, February 18, 2002, http://www.thenation.com/doc/20020218/pollitt, (accessed May 1, 2009).

[12] Pierre Bourdieu, “The Biographical Illusion.” Identity: a Reader, ed. by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman, (London: SAGE Publications, 2000), 297.

[13] Pierre Bourdieu, “The Biographical Illusion.” Identity: a Reader, ed. by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman, (London: SAGE Publications, 2000), 300.

[16] Scott McLemee, “Locating Bourdieu,” Inside Higher Ed, June 23, 2005, 1. http://www.insidehighered.com/views/mclemee/mclemee38, (accessed May 16, 2009).

[17] Anthony Giddens, “The Trajectory of the Self.” Identity: a Reader. Edited by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman, (London: SAGE Publications, 2000), 262.

[18] Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death, ed. Howard V. Hong, trans. Edna H. Hong, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980), 49.

[20] Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death, ed. Howard V. Hong, trans. Edna H. Hong, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980), 66.

[22] Anthony Giddens, “The Trajectory of the Self.” Identity: a Reader. Edited by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman, (London: SAGE Publications, 2000), 249.

[24] Anthony Giddens, “The Trajectory of the Self.” Identity: a Reader. Edited by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans, and Peter Redman, (London: SAGE Publications, 2000), 250.

[26] Jean-Paul Sartre, “Existentialism and Humanism.” Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), 601.

[28] Jean-Paul Sartre, “Existentialism and Humanism.” Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), 602.

[31] Berys Gaut, “Identification and Emotion in Narrative Film.” Philosophy of film and motion pictures: an anthology, ed. by Noël Carroll and Jinhee Choi, (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2006), 260.